Zakiram: Unraveling the Multifaceted Protector Goddess of Tibetan Temples

Tibetan Buddhism is celebrated for its rich pantheon of protector deities—venerated figures whose legends blend local folklore with Vajrayāna teachings. Among these, Zakiram (扎基拉姆)—often honored as the guardian goddess of Zhaqi Monastery—stands out for her many faces and roles. In her, wealth, health, and protection intertwine, reflecting Tibet’s unique blend of spiritual inclusivity and cultural exchange.

A Pantheon Built on Inclusion

Unlike strictly hierarchical mythologies, Tibetan Buddhism’s protector deity system welcomes spirits and gods from diverse origins. Local Tibetan, Bön, and even Hindu figures find new life as Dharmapālas (Dharma protectors), provided they align with Vajrayāna’s compassionate vows. This openness has allowed a figure like Zakiram to evolve from regional lore into a temple’s central guardian.

Zakiram’s Many Faces and Functions

Zakiram is more than a simple “god of wealth.” Devotees praise her for:

-

Prosperity and Generosity

As a Tibetan wealth goddess, she ensures the material well‑being of families and monastic communities alike. -

Career Success

Zakiram’s blessings extend to livelihood and honorable work, guiding artisans and traders. -

Health and Protection

In her fierce aspect, she wards off illness and malign spirits, preserving both body and spirit. -

Inner Strength

Her transformational legends teach practitioners to overcome jealousy, attachment, and pride—inner demons as real as any external foe.

By integrating these roles, Zakiram exemplifies the multi‑functional nature of Tibetan protector deities.

The Origin Tales: From Palace Intrigue to Temple Guardian

One popular legend traces Zakiram’s origins to the Qing dynasty court. She was said to be a favored consort of Emperor Qianlong. Court intrigues led to her poisoning by jealous rivals. Though her body perished, her spirit endured. A visiting Gelugpa lama—known variously as Jamyang Mirang or Sorjibonji—recognized her wronged soul. Through compassionate ritual, he guided her to Zhaqi Monastery in Lhasa, where she was installed as the temple’s guardian.

Other versions highlight her arrival from Baltistan (modern-day Gilgit-Baltistan), where similar “chicken‑footed” deities abound. Her talons—often sculpted as gallina feet—remind us that cultural currents have long flowed between Tibet and its western neighbors.

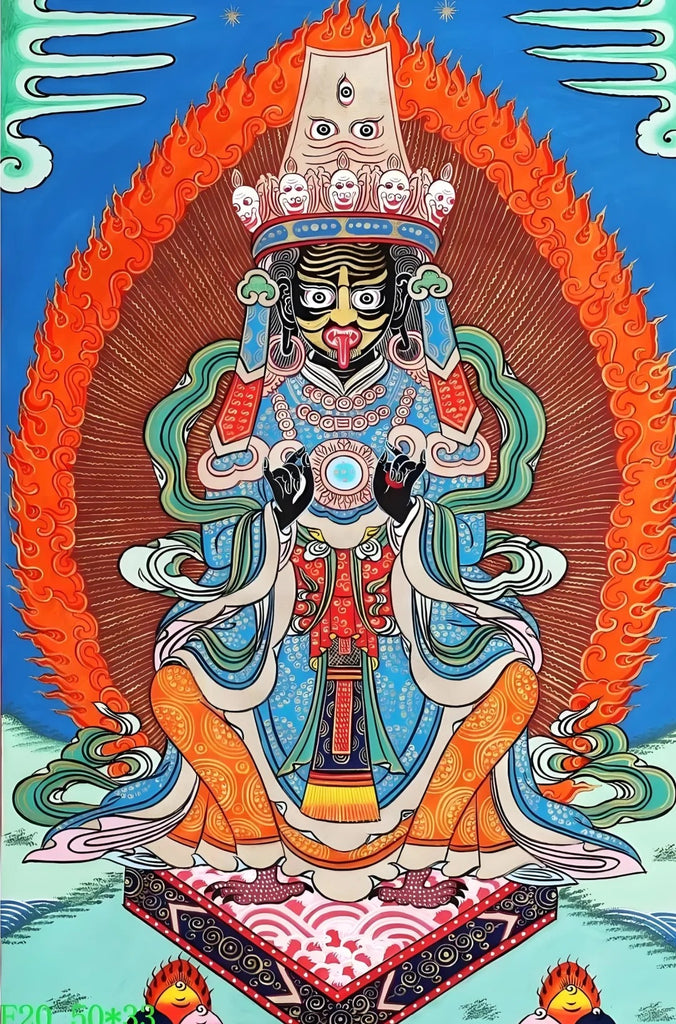

Iconography: Wrath Meets Benevolence

Zakiram’s statues and thangka paintings are striking:

-

Dark Complexion & Fierce Countenance: A reminder that protection sometimes wears a wrathful guise.

-

Skull Crown & Bone Ornaments: Symbolic of conquering ego and impermanence.

-

Chicken‑Footed Stance: Tied to Baltistan motifs, suggesting early cross‑cultural exchange.

-

Tongue Extended: According to legend, a poisoned tongue grew long—later artistic restorations softened this feature, but it remains a mark of her survival.

This complex iconography invites both awe and intimacy, capturing Zakiram’s dual power to destroy obstacles and bestow blessings.